I took my daughter to Barnes & Noble at the Irvine Spectrum a few weeks ago. She’d just finished the entire Harry Potter series, every word read and listened to. It was time for a new adventure. She ended up with Percy Jackson and the Olympians: The Lightning Thief. I wandered over to nonfiction, looking for a book that might turn into a newsletter.

That’s when I found Give and Take by Adam Grant.

I’ve shared Grant’s work, Think Again and Hidden Potential, in our webinars and book reports in the past. But this one hit me on a more personal level. It didn’t just teach me something new. It made me reflect on who I used to be and who I’m trying to become.

Three Types of People and the Risks That Follow:

In Give and Take, Grant identifies three categories: takers, matchers, and givers.

- Takers put their interests first, even if it harms others.

- Matchers believe in fairness: “I’ll help you if you help me.”

- Givers help without expecting anything in return.

Grant explains how takers often rise quickly. He uses Ken Lay of Enron as an example. Outwardly charming, generous, and community-focused. But it was a mask. Behind the scenes, Lay drained value from others to prop up a collapsing system. When it fell apart, the damage was massive and personal for those who trusted him.

Matchers? They’re more common. They’re not harmful, but they don’t build trust either. They keep score. You’re either square with them or you’re not.

Then came the givers like Adam Rifkin, a quiet Silicon Valley engineer who made hundreds of introductions, gave feedback, and mentored entrepreneurs. He didn’t want anything in return. His reward was a stellar reputation. And in many circles, your reputation is your greatest asset.

The Dangerous Twist in Giving

But Grant offers a twist. Not all givers thrive. Some give too much. Some give for the wrong reasons. Some can’t say no.

That’s where things get risky, especially in our white-collar crime community.

I’ve lost count of how many people told me, “I didn’t have bad intentions. I got swept into something.”

They didn’t want to say no. They didn’t want to disappoint. And before they knew it, it was The United States of America vs. [Their Name].

There’s a name for healthy givers: other-ish givers. They help without losing themselves. That’s what our team at White Collar Advice strives for.

Looking Back at My 20s and the Men I Admired

Reading Grant’s book forced me to reflect.

In my 20s, I was a taker. I only helped people if it helped me. I was all in if someone could connect me to money or influence. I mentored people only if I thought it made me look good.

I admired the wrong people, men with accolades, money, and high-status jobs. But they were on their third marriages, drinking before pulling into their driveways, spending more time at country clubs than with their families. They created fake business trips to avoid being a husband and father. I thought they were successful. I didn’t ask what it had cost them.

Worse, I was becoming like them.

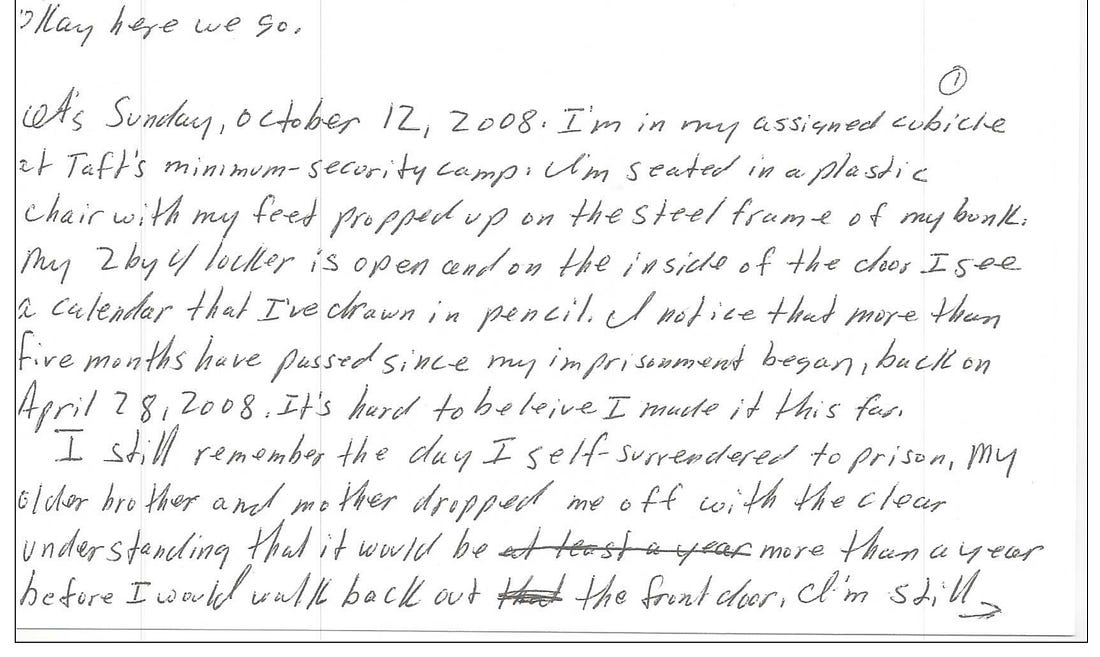

The Shift Happened in Prison October 12, 2008

You may know this story if you’ve read Lessons from Prison. When I surrendered, I had no plan. I just wanted to “not waste time.”

That changed on October 12, 2008.

Michael Santos helped me write my first blog from prison. That blog, posted with no real expectations, started something. It helped people. And it gave me purpose.

I didn’t even know it at the time. That’s when this business launched.

I saw other prisoners going home scared. Their spouses were asking, “How are we going to live? You can’t go back to your job. What’s your plan?”

Most had no answer. That’s when I knew I had to do something different.

So I wrote. Every day. And people noticed.

The Power and Cost of Showing Up and Giving

Writing every day had a price. Some people mocked me. “You only served a year. You’re not qualified.” Others felt exposed. Their spouses would send them my blogs: “Why aren’t you doing something productive like this guy?”

Some will find value in it. Perhaps some will not.

But I kept going. I wasn’t doing it for praise. I was doing it to help.

Michael modeled that kind of giving. I’ll never forget when he told my parents during a visit: “Your son’s doing great. He’s planning. You should be proud.”

That moment brought my mom to tears, for the right reasons.

I will tell you the benefit of being in prison and writing that blog was that I could send it out to the world, and I had no internet to see what people said or responded to. It’s in the lock box. It’s gone. My mom would say, “You’re getting comments.” And I’d reply, “No comment right now is going to change what I create. It’s fine, for now, I don’t want to be influenced. I won’t read them until my release.”

Giving Without Boundaries Isn’t Noble. It’s Dangerous.

Let’s be honest: not all giving is healthy. Today, I still get requests every day.

“Can you review my sentencing letter?”

“Can you help with my probation interview?”

We give away a lot: books, blogs, podcasts, weekly webinars, videos, checklists. But we also have to say no. We focus our time on people who hire our team and are serious about preparing (not just for sentencing), but the rest of their life.

Never forget, saying no isn’t selfish. It’s clarity. It’s healthy.

Matt Bowyer: The Quiet Example of a True Giver

Matt Bowyer pleaded guilty in the Shohei Ohtani betting case. He was due to be sentenced on his 50th birthday in April, but the date has been pushed to the fall. Most people in his position would be frozen. Instead, Matt’s building and inspiring.

He’s a husband and father of five. He went from making millions to selling artificial turf. Yet, he’s grateful for the work. Not bitter. Not sulking. He shows up every day. And he gives.

He’s open about the mistakes he made. He doesn’t run from it. He’s not hiding. He’s not obsessed with spinning a narrative or avoiding judgment. He’s doing the work to rebuild, as his Instagram profile proves.

He talks to other defendants. Offers ideas. Helps people focus on what they can control. I’ve watched him take calls from people facing indictment, sitting with them as they try to make sense of what’s happening. No rush. No clock. He gives them time they didn’t earn and advice they can’t find on Google.

At least ten people have contacted us asking, “Can I speak to Matt? How is he staying so positive?” Every time, he says yes. He never asks for money. He shares his experience. His energy. His time. He speaks openly about the pressure, the fear, the conversations with his wife Nicole, the reality of possibly going to prison.

One father told me after a call with Matt, “That conversation saved my sanity. I was spiraling. He reminded me who I am.”

Matt doesn’t work for White Collar Advice. He doesn’t get paid. But he’s exactly what a giver looks like. And I believe it’s one reason he’s so composed and confident, even with sentencing ahead. He’s not waiting to contribute. He’s already contributing.

I shared this quote from our “Just Try Newsletter” last week and am urged to share it again. Carl Jung said:

“The world is full of people suffering from the effects of their own unlived life. They become bitter, critical, or rigid. Not because the world is cruel to them, but because they betrayed their own inner possibilities. The artist who never makes art becomes cynical about those who do. The lover who never risks loving mocks romance. The thinker who never commits to a philosophy sneers at belief itself. And yet all of them suffer because, deep down, they know they missed their moment.”

I saw that in prison. I see it outside, too. People mock others for trying because it reminds them they stopped trying.

Focus on giving, as Michael, Matt, and our entire team strive to do; ignore those who missed their moment.

The Baseball Talk That Brought It Home

I took my son to a USC baseball game a couple of weeks ago. They’re playing at the Great Park in Irvine while they rebuild the stadium for the 2028 Olympics. On the drive over, he asked, “What was the best lesson you learned from baseball?”

I told him the truth. It wasn’t learning how to win, we won a lot. It was learning how to fail publicly. Repeatedly.

Striking out with the bases loaded. Making the game-ending error. I remember one game against the Japanese national team I went 0 for 5 with three strikeouts. I knew what pitch was coming. We had the signs. Still couldn’t hit. But I came back the next day, and kept contributing.

I didn’t know if I’d ever start again (I didn’t). But I kept showing up. And that’s what I want from all of you.

Final Questions and a Simple Ask

Ask yourself:

- What are you giving without expecting anything back?

- Why are you still saying yes when you know the answer should be no?

- Who are you trying to please at your own expense?

- What would you create if you weren’t afraid of being judged?

- What’s the cost of putting it off any longer?

You can read my first blog from prison, on October 12, 2008 here. It’s not perfect. But it was honest and I had good intentions.

You don’t have to wait until you’re under indictment or in prison to start giving in a smarter, more focused way. You just have to start.

I’m grateful you’re here, that you’re giving me your time. I’ll say it again: my only regret is that I had to go to prison to decide to give back and become the person my parents raised me to be.

Justin Paperny