October 2008, Cheesecake, Root Beer, and a Terrible Idea

“Bud, are you serious? You’re telling me you want to stay in prison longer?”

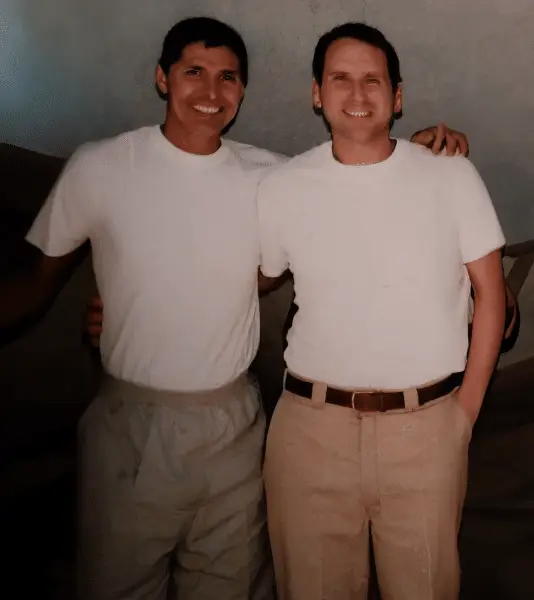

That was Sam Pompeo, across from me in the Taft visitation room, Root Beer resting on the table, cheesecake already half gone.

I told him, “Yeah, I’m totally serious. My mom will probably freak out. It would just be an extra three months or so. I can do it. I’m making such progress here. And I kind of have to seize the opportunity.”

Sam wasn’t just another visitor. He’d been one of my closest friends since 1998, when he sold me my first home in Studio City. We’d been through plenty of ups and downs together. The day I was fired from UBS in January 2005, he was the first person I called. His response wasn’t hesitation; it was insistence: “You’re joining me in real estate, starting now.”

When agents in his office complained about letting someone under investigation work there, Sam didn’t flinch. His reply was simple: “Please mind your own business.”

I’ve said it in interviews many times: all you need is one friend like Sam to get through a crisis. I was looking forward to this visit, even if it started with him telling me, “Bud, get it together. You need to get the hell out of here and come back and sell real estate with me.”

I couldn’t blame him for being confused. From the day I got fired at UBS on January 15, 2005 to the day I surrendered to prison on April 28, 2008, he had watched me unravel in slow motion.

“Sam, you remember when I was lying on the floor in your office after I learned I was a defendant? Then I left your office and went to Johnny Rockets for the double cheeseburger, chili cheese fries, and a shake while I chain-smoked outside. That wasn’t normal. That wasn’t healthy. I was a disaster.

“Then I sat on your couch for a month before I went to prison, asking you to make me grilled cheese and chocolate shakes. It wasn’t a good look.”

That month summed up my crisis response: hide, eat, stall.

“Sitting here now, I can’t believe how naïve I was. I honestly thought doing nothing after the FBI showed up was some kind of strategy. The truth is, I was hiding. I just wanted this to go away. And for a while, I thought it worked.”

And since I’ve been here, listening to similar stories, I know I wasn’t alone. Sam, it’s the same story with every guy here. Different crimes, same regret. Every one of them says the same thing: I wish I had acted sooner. I wish I had built something for sentencing, led better for my family, and learned how to hold those damn lawyers accountable. I wish I had done more to stress why I am different than my plea or DOJ press release.

“I was no different than 15 of my fellow prisoners, you see, sitting in this room. Too many of us walk around the track saying, ‘What I would do for a do-over.’”

The Suit Cost $1,500. The Lesson Was Priceless

“Remember my sentencing? I was still in fantasy land that perhaps through luck, not merit, I could avoid prison.”

That changed in about four seconds when victims with rage in their eyes filled the front row, demanding I go to prison. And what was going through my mind when I saw them? First, what the hell are they doing here? They got all their money back. Second, this damn suit I just bought is already too tight. I just bought it, and the buttons were popping off. Rather than show any empathy, I wondered if the suit was fixable. And I did my best to ignore my mom, who was there. I was grateful my dad didn’t attend.

Judge Wilson didn’t mince words. He looked right at me and said he was tired of salesmen turning the other way for money. Most don’t get caught. I did. And then he said he was going to make an example out of me.

Victims in the front row practically started popping Cristal. After sentencing, while I was in the bathroom trying to fix my suit, a victim’s son told me, “Don’t drop the soap in prison.”

All I thought was, “A corny prison joke? That’s what you’ve been waiting to tell me?”

In retrospect, I can’t blame Judge Wilson. He did his job. I did nothing to change his perception of me: I sat back and let the Department of Justice, with their unlimited resources, do my branding and marketing.

The Visiting Room: Boredom, Bad News, and Broken Plans

Sam looked around the visiting room and changed the conversation. This was a lot for him to take in, that much I knew.

“I’ll give you this,” Sam said.

“It does look pretty laid-back here. Not a terrible place to visit, huh?”

“Yeah, it’s terrific. Look, all things considered,” I said, “It’s an easy environment. Nothing like you see on television. The biggest problem here is boredom; no violence unless you break some of the unwritten prison rules.”

The hard part for a lot of guys is visitation; they aren’t all they’re cracked up to be. They get a lot of bad news from home. Children are struggling without their dad. Bills aren’t being paid. Someone comes back every week to say their wife is leaving them. I have it easier, I know, without a family and kids. Whenever I think I have it bad, I just look around me.

By October 2008, I had been at Taft for five months. I had seen enough to know I wasn’t unique in how poorly I prepared for sentencing and prison. Yet beyond the regret we all felt, I noticed something else happening: fear.

I told Sam, “I see good guys scared to go home, unsure how they will sustain themselves without a medical, law, or accounting license.

My friend Alex, who I do pots and pans with frequently, says: ‘All I think about is the money I made, legally, before I broke the law. Now, I start over with nothing. I almost wish I never made it since I know what it is like to have it. What the hell do I do now?’

Men are turning down visits, turning down the halfway house, and a few have actually gotten disciplinary infractions on purpose to lose some of their good time credits.”

“It is sad to hear so many of these stories. I don’t understand some things you said. What is good time?” Sam asked.

“Good time is 15% they give us off our sentence for essentially not doing anything wrong. At 18 months, I got 2 months and 21 days.”

“How do you lose good time or get in trouble?”

“Oh no, here come the prison questions. We need to focus on the big stuff here. We both know my mom is going to call you the second you leave this visit with a hundred questions about what I will do when I leave. Last week, she asked how quickly after prison I would get married. We need to plan!”

Sam laughed. “Fair enough. This prison stuff is interesting, though. I sell real estate all day; give me a break. I reserve the right to ask more questions!”

“So you are scared and want to stay in Prison?” he asked.

“I am not scared. Anxiety, yes. But we both know I have it better than most: my youth, home to return to, some resources left, someone like you to work with. What I must solve is this miserable situation I created. I think I know how. Can I tell you?”

“Yes, can I get some more cheesecake first?”

Five minutes later.

“What happened?” I asked.

“Long line at the vending machine,” Sam said.

“You ready?”

“Yes!”

“You see that person over there in the corner?”

“Yes.”

“That’s Michael Santos. We’re in the same dorm. No joke, he’s been inside for 22 years. Twenty-two years.”

Sam shook his head. “How can he even be in a camp? I thought camps were for people with short sentences.”

“Good God, more prison questions! Let’s keep going. This guy gets up at 1 a.m., writes until 7 a.m., runs 10–15 miles, then teaches classes every day at the warehouse behind the commissary. He’s constantly producing. He gets invited to contribute to books from Stanford Law School and Princeton. He’s written more books than I can count. He has more discipline than any athlete I’ve seen. And he’s mentoring me.

He asks me questions I can’t answer, and that’s bad. ‘What is success for you? What outcome are you trying to engineer?’

When I couldn’t answer, and sensing that I wanted something better for my life, he agreed to help me. He’s encouraged me to read dozens of books. A passage in one helped me recognize the opportunity I had to learn from him.

Machiavelli wrote in The Prince: ‘A prudent man will always try to follow in the footsteps of great men and imitate those who have been truly outstanding, so that, if he is not quite as skillful as they, at least some of their ability may rub off on him.’

“Michael is that great man for me. As Machiavelli would put it, he’s the one I’m following. I’m not him, but if I imitate him, maybe some of it rubs off. Maybe I can find a path on the other side of these prison boundaries to help others and myself.”

“Who’s Machiavelli?” Sam asked.

“You’re Italian, you should know Machiavelli. Someday I’ll go see his tomb in Florence.”

Sam grinned. “Bud, did you just read me an exact quote from this Prince Machiavelli character?”

“No; the name of the book is The Prince, written by Machiavelli; and yes, that’s the exact quote. I’m reading, learning quotes, and trying to understand them. Most of them I don’t. The ones I do, I build into my vocabulary. So I’m going to start using some words that might sound out of place. By using them, I learn. I’m striving to become more insouciant in prison.”

“Do you even know what that means?”

“Bud, you’ve used six words in this visit that I do not understand.”

“This the feedback I need. I may be overdoing it.”

The Stoic in the Quiet Room

My rant continued.

On the track last week, Michael handed me Epictetus. Naturally, I didn’t understand most of it, but I did understand this line: “We cannot choose our external circumstances, but we can always choose how we respond.”

“I couldn’t control the press release. I couldn’t control the victims in the front row. But I can control what I do now. For three and a half years, I did nothing. Now, I want to follow Michael’s lead. I want to build an online record that shows how I’m owning this mess I created. I want to help others who are drowning the way I was. I want to give rather than take. I want to be useful.

I’m not naïve. Some people hated the writing idea immediately, a few guys clearly resent the time I spend with Michael. But I don’t care. At 4 a.m., I join him in the quiet room, working. This isn’t about them. It’s about making sure my 18 months don’t become a life sentence. The only way forward is to create, to keep writing, to keep trying.”

Sam leaned back, still trying to process it all. “Wow, this has been quite an experience so far.”

I nodded. “And think about it, I’ve only been gone five months. Truth is, I wasted the first two just exercising all day. Imagine if I had started preparing the very first day in prison? Or better yet, on April 28, 2005, the day the FBI showed up at my front door?”

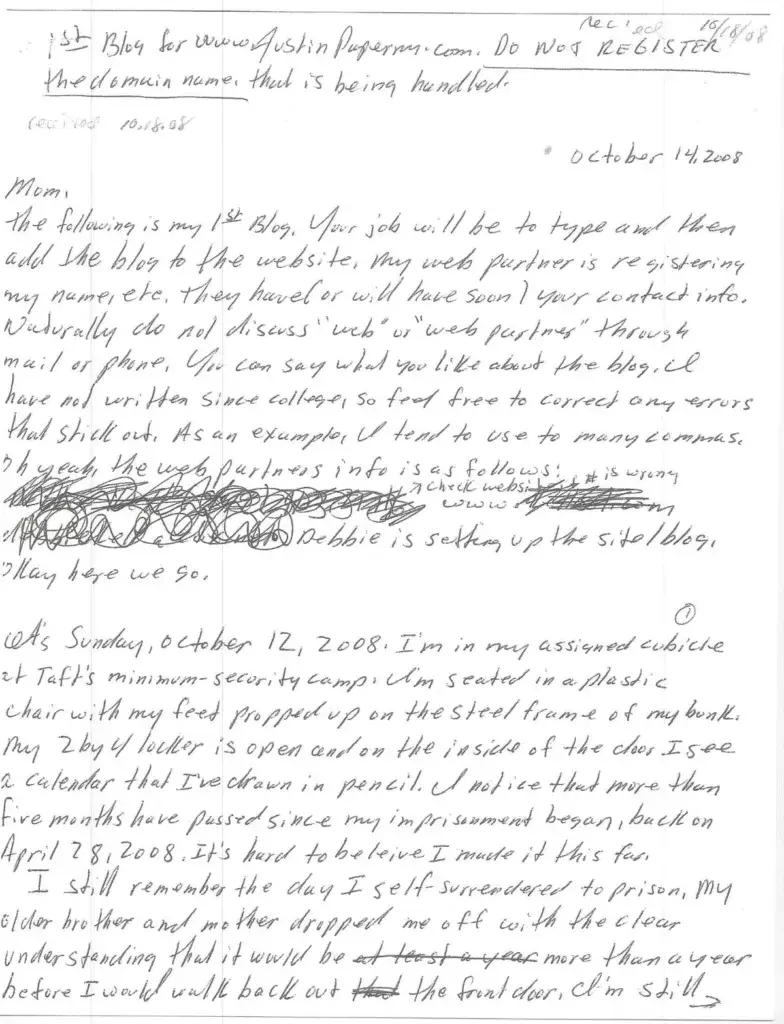

October 12, 2008: One Blog, One Envelope, One Promise

A week after that visit, Michael and I sat in the quiet room. With his help, I wrote my first blog.

When we finished, I sealed it in an envelope to mail to my mom.

Before I dropped it in the box, Michael stopped me.

“The end of this blog says you will write daily. Is that a commitment you can fulfill?”

“Yes,” I said.

The Mockery: Tourist, Fraud, or Writer?

While I imitated Michael, my writing had to take a slightly different approach. He had been writing on MichaelSantos.net for years, teaching people how to succeed in prison, emerge with dignity, and overcome adversity.

One year in prison isn’t “overcoming adversity.” Not when you’re timing your laps in a minimum security camp. What I wanted to do was share my insights from prison, from my perspective as a former stockbroker who had blown it in spectacular fashion and was now living with the consequences.

I didn’t know exactly what would come from the blog, but I was committed to writing daily, even if the only value was showing my family I wasn’t wasting the time.

Some mocked me. Staff said I hadn’t been in long enough to write about prison. A few prisoners rolled their eyes: “Tourist. You’re in for a year. You don’t know what real time is.” Others resented that their spouses were reading my blog and asking, “Why aren’t you doing something like this guy?” That didn’t make me popular.

My family pushed back too. They didn’t want me to write about prison. Not because they were ashamed, but because they wanted me to move on. They wanted me to box it up, serve the time, come home, and act like it never happened. They didn’t understand, not yet, that writing was the only way I could process the experience, find meaning in it, and maybe offer something to the guy who, like me, drowned his stress at Johnny Rockets or to the father who was hiding in his man cave, avoiding his kids’ little league game.

And some people loved it. About a month in, letters came back in the daily mail call. Too many, in fact. A guard would call my name, and I’d walk back with a stack. It triggered envy in the unit. Men saw it and hated me for it. I understood. I’d lived with that same envy as a defendant, watching others move forward while I spiraled.

I didn’t complain about the mockery to anyone. Certainly not to Michael, he’d been inside for decades and endured unimaginable trauma that comes with going to prison for 45 years at 23 years old.

Instead, I noticed something changing in me. As a defendant, I overreacted to everything: every email from a lawyer, every legal bill, every phone call, every headline. Now, I felt desensitized. Almost numb.

It can be dangerous, in a good way, when you reach a point where you feel like you have nothing left to lose. By then, my old decisions had already failed me. My reputation, my career, my freedom, gone. What did I have to protect? And in that vacuum, mockery lost its sting. Instead of shrinking me, it emboldened me. Oddly enough, the more pushback I got, the more certain I became I was finally on to something. I sort of liked it.

That’s one of the hidden benefits of prison, if you use the time wisely. You stop living for other people’s approval. You stop worrying about whether everyone likes it. You focus on doing the work, regardless of the hate, envy, and the constant noise.

February 2009, 100 More Days Until My Release From Prison

By February 2009, I had been writing for six months. Every night, another envelope slid into the mailbox. My mom typed them all. Some people rolled their eyes. But the blogs kept going out. Lessons From Prison was nearly complete.

Sam made the drive back to Taft. Same plastic chairs, same cheesecake. But this time, his tone was different.

“Hey, man, you’ve made a lot of progress since October. I read most of your blogs.”

“Not all of them?” I shot back.

“Bud, the real estate market is crashing. Pretty clear you chose to sit out this recession in prison! I read most, and I share them with people in the office. I didn’t fully get what you were planning in October, but it’s clear now, you want to help people the way you wish someone had helped you when you were so off your game.”

He paused, then added, “I’m proud of you. It’s remarkable how much you’ve done since you’ve been in prison. You were right, you were very fortunate to meet Michael and learn from him.”

This time, without having to say it, Sam knew I appreciated his support. I was ready to change the conversation.

“Hey, some good news,” I told him. “I’m taking the halfway house. I’m ready to come home. There’ll be ups and downs; everyone has ups and downs, but I’m ready to start the next phase of my life. I’ll see you on May 20. It’ll be here before you know it.”

Sam shook his head. “Bud, you’re something else. I believe in you. I will always be here to help.”

“I know,” I said. “To that end, I need a job when I get out of here. I’ve already written the draft employment letter. It’s in the mail to you. Please approve it, put it on your company letterhead, sign it, and send it back. I want to send it to my probation officer.”

“Done,” he said without hesitation.

That was Sam: no drama, no second-guessing, just loyalty. The same loyalty he’d shown when others ran back in 2005.

Back in October, he thought I was out of my mind for wanting to stay. By February, he could see it, I wasn’t waiting anymore. I was doing the work every day. And now, finally, I was ready to come home.

Reflection Journal

When I finally stopped hiding, I realized silence had been its own kind of sentence. For three and a half years as a defendant, I let the DOJ, the press, and other people tell my story. I didn’t give them anything else to balance against it.

If you’re honest with yourself, where are you right now? Are you sitting quietly, hoping it all goes away like I did? Are you letting other people write the version of you that will live online, in court, or in the minds of your family?

Write it down. Be specific.

- What “silence” looks like in your life today.

- What story would someone else tell about you if they had to write it right now?

- One thing you could create or document this week that shows you’re more than that version.

Don’t write what sounds good. Write what’s true. Even if it stings, it will give you something to work with.

Written by Justin Paperny, author of Lessons From Prison and Ethics in Motion.