Our last webinar focused on persuasion: essentially, we must have trust from stakeholders before making a request.

I’ve continued to study pre-suasion because we are covering the same topic again on Tuesday and because I’m developing a really cool timeline that shows how Michael used pre-suasion to build his pathway through prison, culminating with his meeting this week in DC with BOP leadership.

As you likely know, White Collar Advice was the initial funder of PrisonProfessors.org and to this day a percentage of every sale goes to support their mission. We are advocating for more furloughs, expanding earned time credits and creating more mechanisms that allow more people in prison to Earn Freedom.

While working on this timeline, I reflected back to meeting Michael. And that leads us to Scarface. When Michael was in his late teens, before his arrest, he saw Scarface. He didn’t watch it like most people do. He studied it. He admired Tony Montana’s strength, power, and the control he commanded.

That performance (Pacino’s performance) helped drive decisions that compelled Michael to sell drugs. Following his trial, he was sentenced to 45 years in federal prison.

Since my release from prison in 2009, I’ve continued to think about the impact Al Pacino and that movie had on Michael. For that reason, when I saw Sunny Boy, Pacino’s memoir, at Barnes and Noble last week, I picked it up. I wanted to understand the man who had unknowingly influenced my friend’s fall, and by extension, my own life. After all, if Michael doesn’t watch Scarface, he doesn’t go to prison, and I never would have met him. Where would I be now? Certainly not writing this newsletter.

What I found in the book wasn’t what I expected. I suppose I expected a memoir written by a ghostwriter. Pacino, I think, actually wrote this book. Sunny Boy isn’t fully developed. It jumps around. It’s full of reflections, half-finished memories, but real vulnerability and authenticity. He’s not lying or trying to impress you. He writes like someone unpacking a box of thoughts he hasn’t looked at in a long time, like 60 years.

And through his introspective process, something emerged: a picture of a man who knows what it’s like to be cast aside, doubted, and what it means to have someone stand next to you when no one else will.

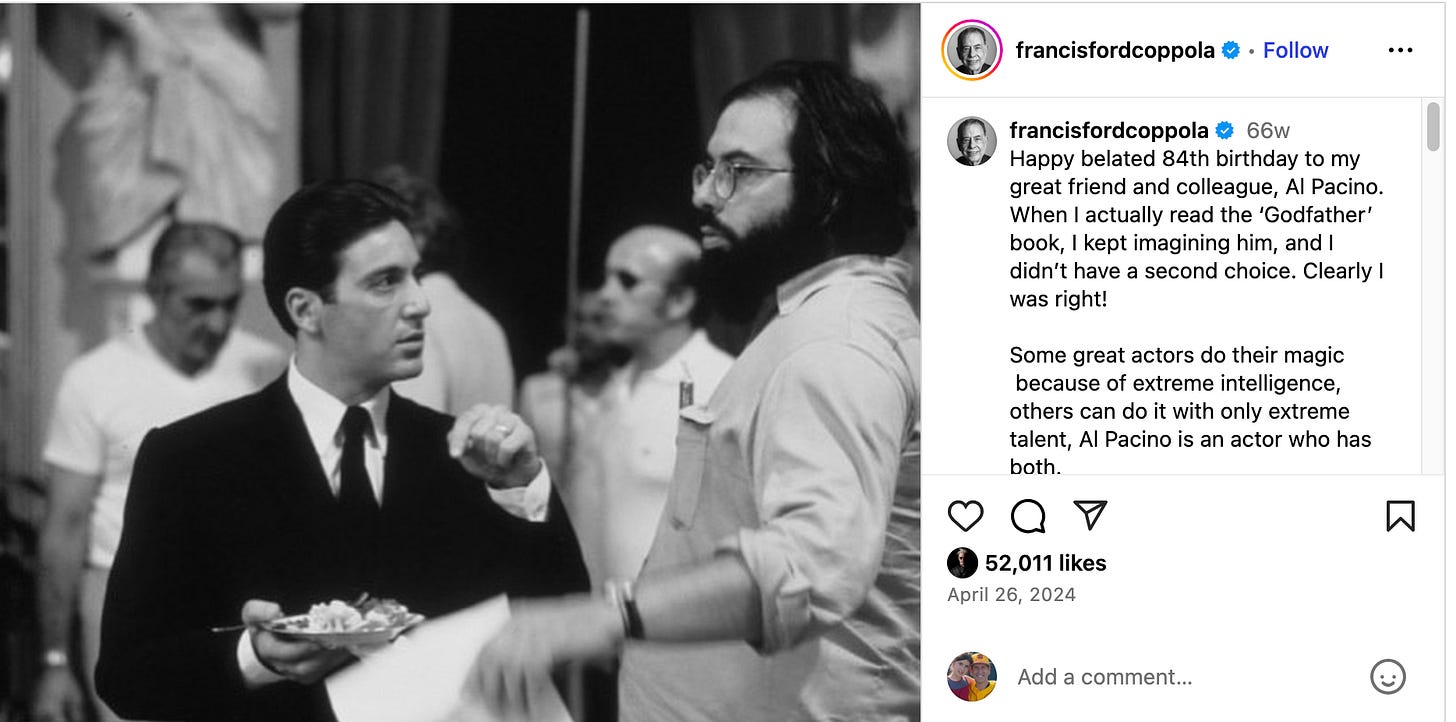

And that’s where Francis Ford Coppola enters.

Sure, he’s famous now and has been for a long time, but when he signed on to The Godfather, he wasn’t a studio favorite. He was young. Unpredictable. Emotionally volatile. Yes, he’d won an Oscar for Patton, but he wasn’t trusted. Paramount wanted a safe director to helm The Godfather. They settled for Coppola because he was affordable and seemed controllable. They figured he’d say yes.

He didn’t.

From the beginning, Coppola fought them. He refused to make a glossy gangster film. He wanted something slower, darker, almost operatic. And he saw something in Al Pacino, something unique, different, that no one else could see.

Pacino had won a Tony Award, but he wasn’t famous. He wasn’t charismatic in a traditional sense. He didn’t look the part. The studio executives thought he was too quiet, too wooden. They didn’t just dislike the casting. They hated it.

On page 113, Pacino writes:

“Paramount rejected Francis’s entire cast for The Godfather, including Jimmy Caan and Bobby Duvall. They even rejected Brando. And it was clear from the moment I walked into that studio, they didn’t want me either.”

As filming began, Pacino recalls the tension of walking onto set each day knowing it could be his last. On page 114, he shares what saved him:

“Francis wanted me. He wanted me. And I knew that… There’s nothing like when a director wants you. It’s the best thing an actor could have, really.”

Francis Ford Coppola protected Pacino. He pushed to keep him. He paired him with Diane Keaton, fought back against the studio, and stood next to him when everything was on the line. When Pacino started to falter, Coppola didn’t walk away.

They tried to fire him.

Coppola resisted. Then resisted again. Eventually, they told him it was over. Pacino was done. The pressure was absolute.

A week into filming, Coppola invited Pacino to meet him at a restaurant, not to have dinner together. Pacino says he stood beside the table as Coppola ate. Then he looked at him and said:

“You know how much you mean to me and how much faith I have in you… But you’re not cutting it.”

Years later, Pacino told ABC News:

“They wanted to fire me when I was on the picture … [during] the shooting, first couple of weeks. Because they kept seeing the rushes, you know, or the footage that was shot, and they kept looking at it and thinking, ‘What is he doing?’ I was so confused at that time, and Francis was so supportive … If it wasn’t for Francis, I would’ve just not showed up one day and said, ‘Hey, look man, I don’t want to be where I’m not wanted.’”

So Coppola made a move that would either save them both or finish them both.

He rescheduled the restaurant scene. The one where Michael Corleone sits across from Sollozzo and McCluskey, retrieves the gun from behind the toilet, returns to the table, and makes the decision that defines the entire film.

It wasn’t meant to be filmed that early. But Coppola knew this was Pacino’s moment. If he could deliver here, the studio wouldn’t be able to fire him.

It’s the scene that cements Michael Corleone’s transformation, from uncertain son to something colder. Pacino plays it small—almost no dialogue. The silence builds. You can feel him calculating. Holding everything in.

Then it happens.

Two gunshots.

A moment of stunned quiet.

And Michael drops the gun.

The footage changed everything. The studio backed off. Coppola kept his actor. Pacino kept his job. The movie held together, and the rest, as the cliché goes, is history.

Then I read this section in Sunny Boy, and it made more sense:

“I felt out of place during this role, and yet I felt I belonged. Strange things to feel at the same time.”

He felt he belonged because someone bet on him when no one else would. And that made me think of my friend, Sam Pompeo.

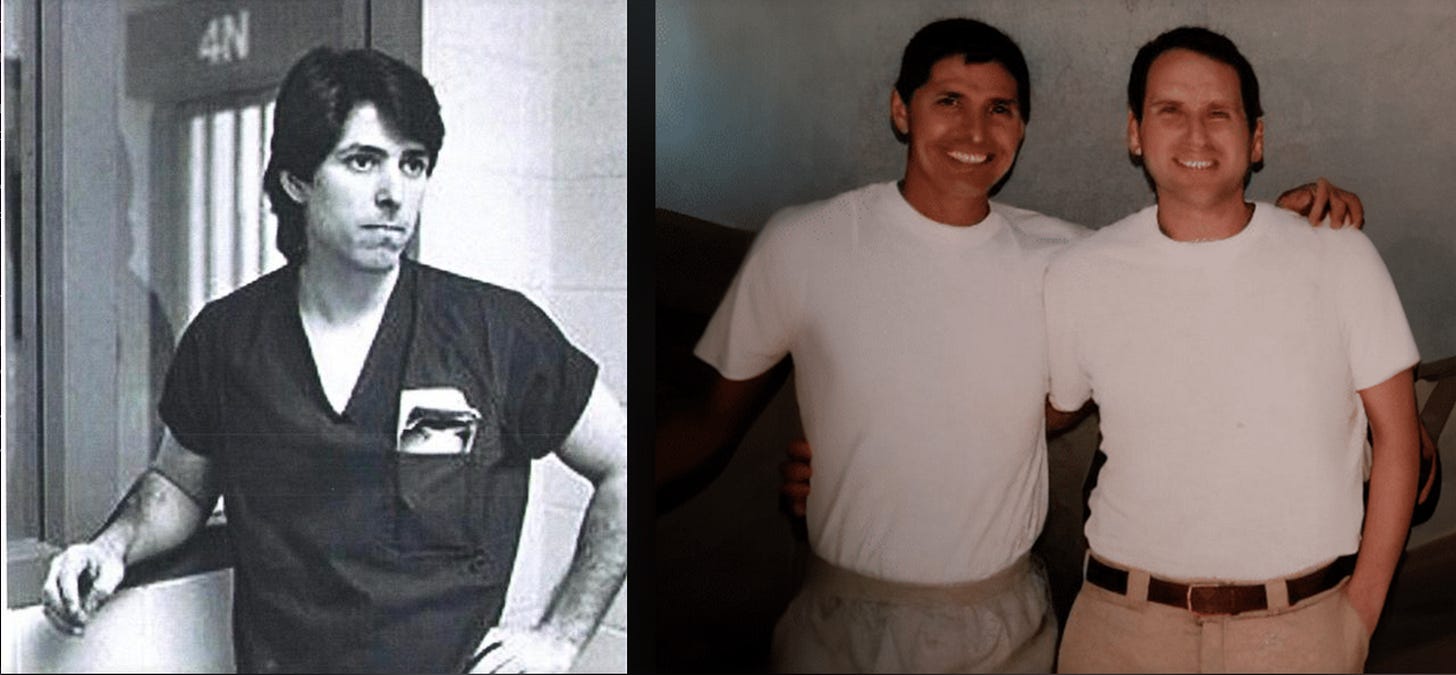

When I was fired from UBS on January 16th, 2005, I lost a lot of friends. Some people were polite about it. Others disappeared. I didn’t blame them. Soon I would be investigated. And in time, I was going to prison. People protect their own reputations. They step back. That’s how it usually goes.

But Sam Pompeo didn’t step back. He didn’t hedge. He didn’t wait to see how it played out. When no one would talk to me, he invited me to join him in selling real estate at Sotheby’s in Calabasas. I was already under federal investigation.

To be more clear, he didn’t hire me. He made me a partner. From the first day, he split commissions 50/50. He put my name on his door. He introduced me to clients who Googled me, saw the headlines. A few walked out. When that happened, he didn’t try to soften it. He just said, “She Googled you,” and we got back in the car.

He stood next to me when there was nothing in it for him but scrutiny. People asked him why. He told them, “Mind your own business.”

Sam stood there while others whispered, and he didn’t flinch. But I know it cost him.

I started documenting his support for me from federal prison. On February 10, 2009, I wrote:

“Sam has been incredibly supportive of me ever since I first learned that I was facing problems with my employer, UBS and then with the criminal justice system… Sam didn’t judge me for the indiscretion I made. He saw that my sense of self was being torn asunder, and he stepped right up to bolster my confidence.”

“Knowing that my troubles would translate into the loss of my career as a financial professional, he sponsored me before his colleagues and insisted that I join him as a full partner in his real estate business.”

“Sam made a point of calling [my parents] regularly after I surrendered to prison. He took my mother to dinner… Sam was more than a friend, he was part of our family.”

“Their support helped me through my journey. It strengthened me to commit to a rigorous adjustment plan, as I wanted to serve my sentence with both dignity and purpose as a tribute to them.”

That kind of loyalty costs something. It doesn’t come cheap. Sam risked his reputation. His income. His future. All for a friend he believed in. I felt a responsibility to do something with the gift he gave me.

I’ve learned a lot since going to prison. You don’t need a crowd or a bunch of people you kind of know, who kind of support you when it’s convenient for them.

You need one.

One person willing to take the heat, make the call, and stay near you when things are hard. That’s it.

Sam was that person for me.

And years later, he’s still here. After my CNN interview about Ghislaine Maxwell, Sam texted me:

“Nice interview on the Epstein co-defendant Maxwell. You’re so eloquent on TV it’s awesome! 👏”

It was a compliment and a return on investment.

He gets to watch someone he believed in do the work.

Coppola and Sam also share something else: no envy. No resentment.

It’s clear Coppola loved seeing Pacino succeed; The Godfather, Scarface, Carlito’s Way, and more. He remained a supporter, a friend, wishing him well.

Same with Sam Pompeo.

I’ll never forget one visit we had while I was in federal prison. At that point, we both assumed I’d return to work with him after I got out. Even if I lost my real estate license (which I eventually did) we figured we’d find a way. I’d help with writing, marketing, and sales pipelines. I just wouldn’t sign contracts or quote pricing. It would’ve been inconvenient, but we could’ve worked around it.

But that Friday, across the table in the visiting room, I told him something different.

I said:

“I’m going to work with Michael. I can’t fully explain the impact he’s had on me, but I think I can find meaning through this experience. I don’t want to hide from what happened or pretend it didn’t. I want to help people like me. With Michael’s guidance, I think I can.”

There was no pushback.

He just said:

“Bud, I support you and want you to be happy. I see the change in you. I don’t fully get it, but I don’t need to. Just tell me how I can help.”

That was it.

I was released to the halfway house on May 20, 2009. I went back to Sotheby’s to work with Sam until my sentence officially ended on August 16.

The next day, my first day on probation, August 17, 2009, I was hired by two people.

And I’ve never looked back.

Same for Coppola. He didn’t just save a role. He helped create a career. And not just any career, one that reshaped film history.

That’s the reward.

And it ties back to what we explored in Atlas Shrugged. Rand made it clear: the creator moves the world. But the creator also needs one believer, someone who sees the value before the rest of the world catches up.

It ties back to The Stranger, too. That isolation. The sense of being emotionally outside the group. The pressure of standing alone. It only changes when one person decides this one’s worth standing with.

Coppola and Sam did that. They made a private decision, took a public risk, and gave someone the gift to rise.

So if you’re facing pressure (shame, sentencing, criticism), who’s still beside you?

And more importantly:

Have you given them anything to be proud of?

Will they feel proud that they bet on you?

Who is a loyal friend or supporter that you can thank today?

Justin Paperny